SassyLassy Sails into Uncharted Waters

ConversesClub Read 2018

Afegeix-te a LibraryThing per participar.

Aquest tema està marcat com "inactiu": L'últim missatge és de fa més de 90 dies. Podeu revifar-lo enviant una resposta.

1SassyLassy

It occurred to me as I was unpacking and shelving books after my 2017 move, that I have a large number with the tag category "Ahoy". Perhaps it's time to get to some of them this year. Will this be the year I finally read Moby Dick?

I'll also be going back to Zola's Rougon Macquart cycle. I had been reading one a month, but only managed one after the move. I'm going to try getting back to one a month as I am almost finished. The next book is the eighteenth. I skipped two as there were no contemporary translations. Hang on - I just checked and there is a new 2017 translation of Une page d'amour, so I have just ordered that. So much for any resolutions about cutting back on book buying this year!

Now that I have moved, I've also started my And Other Stories subscription again, so I'm looking forward to more contemporary fiction from around the world. Naturally there will also still be some reading from the nineteenth century.

2SassyLassy

I love colour and each year, for some obscure reason, I like to start with Pantone's colour of the year. This year it is Ultra Violet, an odd choice as in 2014 it was another purple, Radiant Orchid. Not a repeat though, for Pantone tells us

Who knew? I can go with inventiveness and imagination but the rest seems somewhat overblown in these times. And what is an "intuitive" colour - have apples turned purple? At least they didn't call it Complicit.

Who knew? I can go with inventiveness and imagination but the rest seems somewhat overblown in these times. And what is an "intuitive" colour - have apples turned purple? At least they didn't call it Complicit.

3SassyLassy

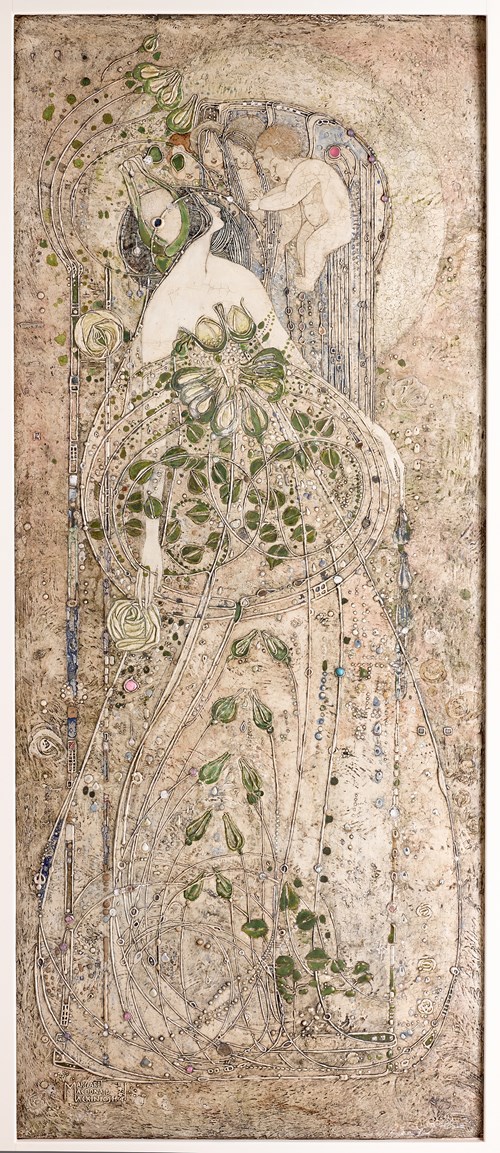

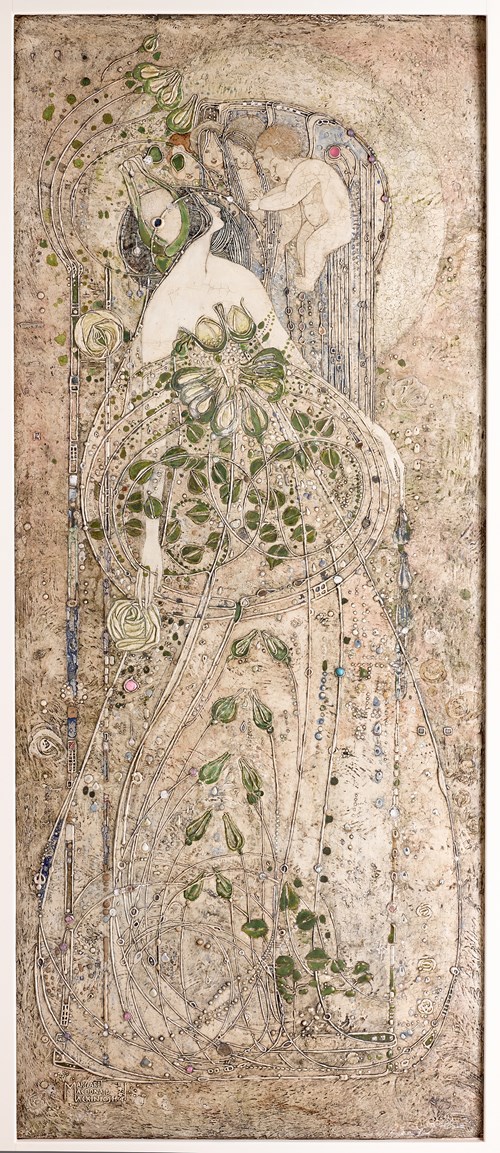

Purple is actually one of my three favourite colours. This is what purple reading looks like:

image from Kitchen Studio of Naples

image from Kitchen Studio of Naples

4SassyLassy

Back to the real world. 2017 was a year of little reading for me. What I did read I usually quite liked, but I didn't get enough reading time in. I hope to change that this year.

2017 saw only 40 books read. The biggest disappointment was that only 30% were in translation into English; I usually average 50% +

Like many in CR, I also read more crime that usual. I'm not sure why, maybe it's better having the bad guys in novels where they get their just deserts.

Lastly, I used to read a lot about the US. Ever since I was a child and saw the cover of Time magazine looking at me each week as my father read it, I've had a fascination with American politics, although I don't live there. This may be the year to delve back in.

______

Edited to correct spelling. The bad guys may get just desserts (hopefully also bad), but I must have been thinking of a favourite eating spot.

2017 saw only 40 books read. The biggest disappointment was that only 30% were in translation into English; I usually average 50% +

Like many in CR, I also read more crime that usual. I'm not sure why, maybe it's better having the bad guys in novels where they get their just deserts.

Lastly, I used to read a lot about the US. Ever since I was a child and saw the cover of Time magazine looking at me each week as my father read it, I've had a fascination with American politics, although I don't live there. This may be the year to delve back in.

______

Edited to correct spelling. The bad guys may get just desserts (hopefully also bad), but I must have been thinking of a favourite eating spot.

5Polaris-

Hi Sassy and Happy New Year! Just starring your thread. There has definitely been something in the air the last year or two - I know so many keen readers who’ve read far less than usual in recent times, including myself. I hope this year is filled with good reading!

6SassyLassy

>5 Polaris-: Yay, you're back! and my first visitor. Here's hoping your reading is works for you too, and pass on any good arbori/horti titles.

7SassyLassy

Forgot to carve out a spot for one of the most useful spots on a thread:

Books Discovered on other People's Threads

NON FICTION

Who Will Write our History? by Samuel D Kassow torontoc

On Color by David Kastan MaggieO

Books Discovered on other People's Threads

NON FICTION

Who Will Write our History? by Samuel D Kassow torontoc

On Color by David Kastan MaggieO

9rachbxl

Happy New Year! I read far less than usual last year as well, and a high proportion of what I did read was crime fiction. My reading has picked up in the last month or so, which I hope is a good sign. I look forward to getting some inspiration from your thread!

10OscarWilde87

Happy New Year!

I see you're maybe approaching Moby Dick this year. It's on my list, too. I'll be interested in your thoughts!

I see you're maybe approaching Moby Dick this year. It's on my list, too. I'll be interested in your thoughts!

11SassyLassy

Here goes with the first book of the year!

1. Rock Crystal by Adalbert Stifter translated from the German by Elizabeth Mayer and Marianne Moore, 1945

first published as Bergkristall in 1845

read January 1st, 2018

I wondered about this little novella as I started reading, but persevered and was rewarded. At first it read like a Christian tract on Christmas and its celebration in the home. Stifter then shifted outdoors, to its setting in a rural village in the mountains of Bohemia. Ever so gradually, he moved further away still, through the woods, avoiding the glacier field, and on to a neighbouring village. All this is done as if taking the reader on a personal tour. He talks about the villagers' habits and stops to point out a memorial to the baker who froze to death on the track between the two villages.

Next, like creating a miniature toy village, he introduces a family with grandparents in each of the two villages. The setting is complete. Just as slowly and deliberately, Stifter moves on to the tale of the two grandchildren one Christmas Eve, alone in the snow that has crept up as gradually as the story itself, as they make their way home from the grandparents in the other village.

Stifter was at one time a landscape painter in Vienna, but he came from a village in the former Austrian Empire. His eye for domestic detail and his knowledge of the land both come out beautifully in this story. You almost want to close your eyes as if it is being read to you.

W H Auden says in his 1945 Introduction to the novel, "To bring off... a story of this kind, with its breathtaking risks of appalling banalities, is a great feat." It works.

1. Rock Crystal by Adalbert Stifter translated from the German by Elizabeth Mayer and Marianne Moore, 1945

first published as Bergkristall in 1845

read January 1st, 2018

I wondered about this little novella as I started reading, but persevered and was rewarded. At first it read like a Christian tract on Christmas and its celebration in the home. Stifter then shifted outdoors, to its setting in a rural village in the mountains of Bohemia. Ever so gradually, he moved further away still, through the woods, avoiding the glacier field, and on to a neighbouring village. All this is done as if taking the reader on a personal tour. He talks about the villagers' habits and stops to point out a memorial to the baker who froze to death on the track between the two villages.

Next, like creating a miniature toy village, he introduces a family with grandparents in each of the two villages. The setting is complete. Just as slowly and deliberately, Stifter moves on to the tale of the two grandchildren one Christmas Eve, alone in the snow that has crept up as gradually as the story itself, as they make their way home from the grandparents in the other village.

Stifter was at one time a landscape painter in Vienna, but he came from a village in the former Austrian Empire. His eye for domestic detail and his knowledge of the land both come out beautifully in this story. You almost want to close your eyes as if it is being read to you.

W H Auden says in his 1945 Introduction to the novel, "To bring off... a story of this kind, with its breathtaking risks of appalling banalities, is a great feat." It works.

12SassyLassy

And because I love illustrations from old books:

The above is an 1853 illustration for the book by Ludwig Richter. I would like to find illustrations by Stifter himself. I'm not sure if this is one or not:

The above is an 1853 illustration for the book by Ludwig Richter. I would like to find illustrations by Stifter himself. I'm not sure if this is one or not:

13SassyLassy

>10 OscarWilde87: "Maybe approaching" is a good way to put it.

>8 baswood: >9 rachbxl: More reading indeed. I know I will be picking up some inspiration from your threads, books to put in >7 SassyLassy: above.

>8 baswood: >9 rachbxl: More reading indeed. I know I will be picking up some inspiration from your threads, books to put in >7 SassyLassy: above.

14RidgewayGirl

May your reading be more ample and satisfactory this year. I look forward to reading your reviews.

15arubabookwoman

Hi Sassy--looking forward to following your reading this year.

Rock Crystal is a book that has been on my wishlist for ages--but I've never come across it in a used book store, and it's not on Kindle. I'm glad you liked it, and I will keep looking.

Rock Crystal is a book that has been on my wishlist for ages--but I've never come across it in a used book store, and it's not on Kindle. I'm glad you liked it, and I will keep looking.

16arubabookwoman

Hi Sassy. I'm looking forward to following your reading this year.

Rock Crystal has been on my wishlist for ages, but I've never come across it in a used book store and it's not available on Kindle. I'm glad you liked it, and I will keep searching.

Several years ago I read a book by Tarjei Vesaas that in my imagination is similar, The Ice Palace. Have you read it?

Rock Crystal has been on my wishlist for ages, but I've never come across it in a used book store and it's not available on Kindle. I'm glad you liked it, and I will keep searching.

Several years ago I read a book by Tarjei Vesaas that in my imagination is similar, The Ice Palace. Have you read it?

17SassyLassy

>14 RidgewayGirl: Thank you - "ample and satisfactory" is a wonderful thought.

>15 arubabookwoman: My edition is an NYRB classic. I just checked their website to see if it was still for sale, as I only bought it last month and discovered it is actually on sale in the US: https://www.nyrb.com/collections/classics/products/rock-crystal?variant=10949311...

>15 arubabookwoman: My edition is an NYRB classic. I just checked their website to see if it was still for sale, as I only bought it last month and discovered it is actually on sale in the US: https://www.nyrb.com/collections/classics/products/rock-crystal?variant=10949311...

19tonikat

avast me hearty, best wishes for your ultra violets (is that in brave new world? or no maybe Lana del Rey). I've marked ye spot with a golden star and will try to keep up, argh.

(edit - meant A clockwork orange not bnw)

(edit - meant A clockwork orange not bnw)

20ELiz_M

>11 SassyLassy: This sounds eeirily familiar, but I am sure I haven't red it yet. I will keep an eye out and add it to my nyrb collection.

>16 arubabookwoman: It is in the Brooklyn Public Library overdrive catalog, the kindle ebook was released in 2015. :)

>16 arubabookwoman: It is in the Brooklyn Public Library overdrive catalog, the kindle ebook was released in 2015. :)

21avaland

I'm always happy to see the annual posting of the Pantone color. Ultra Violet: another delicious color (oh, there are so many!)

Looking forward to following your reading this year.

Looking forward to following your reading this year.

22dchaikin

you left me fascinated by Rock Crystal, a book I'd never heard of. Wondering, a silly geologist might, how much the title is directly addressed in the book. Hope you do get to Moby Dick and in state of mind that lets you appreciate its playful openness...speaking as one who doesn't always manage that state. But, more than that, wish you a great reading year.

23arubabookwoman

>17 SassyLassy: and >20 ELiz_M:--Thanks for the info. My problem was just that I didn't want to pay full price for a new book or the full $10.99 Kindle price. I guess I will break down one of these days since it's been on the WL so long. (My library does not have the Kindle version--off to see if they have a book version.)

ETA Nope.

ETA Nope.

24SassyLassy

>8 baswood: Looking at your Moby Dick review, I am wondering about reading it. I know I will, but it will be interesting to compare with your review and Dan's.

>22 dchaikin: "Silly geologist" - never - we all should know more about the ground upon which we stand. There is not actually much rock description other than topography, but there are descriptions of crystals in the form of glacial caves.

>19 tonikat: Makes me think more of with a Lou Reed vibe. My other self thinks of my garden in spring.

with a Lou Reed vibe. My other self thinks of my garden in spring.

>22 dchaikin: "Silly geologist" - never - we all should know more about the ground upon which we stand. There is not actually much rock description other than topography, but there are descriptions of crystals in the form of glacial caves.

>19 tonikat: Makes me think more of

with a Lou Reed vibe. My other self thinks of my garden in spring.

with a Lou Reed vibe. My other self thinks of my garden in spring.25tonikat

>24 SassyLassy: I can like totes see that. But a garden in spring, ahhh not arghhh, somewhere over my rainbow in Wordsworthian silence, stillness.

I do like this shade, btw.

I do like this shade, btw.

26dchaikin

>24 SassyLassy: just looked up my Moby Dick review, from 2012. I didn't post on the book page, maybe because it's rambling and not particularly enlightening. Maybe i'm just critical in hindsight. If you get to a point you want to read it, you can find it on my 2012 thread here (you might just skip to my last paragraph)

also, this makes me think of lost LTers. Among the response were posts by Poquette and StevenTX. I miss them.

also, this makes me think of lost LTers. Among the response were posts by Poquette and StevenTX. I miss them.

27mabith

Good luck getting to the books you want to and avoiding adding too many to your library. I'd be happy to have a proxy in regard to diving into US politics... It's been so personally scary that other than keeping tabs on my local elections I have to avoid it.

28SassyLassy

>26 dchaikin: Thanks for putting in that link. I can't believe it was that long ago. It is sad to see the responses from people who no longer post. I was very sad to see steven's thread disappear completely.

Your review does make me more hopeful about reading it. I'm not sure what the hesitation is. I read it in my early teens and thought it was a great adventure. For the past few years, I've thought it could do with a rereading but now it seems fraught with so much literary baggage. Maybe it's better not to know these things when we read.

>27 mabith: My first step has been ordering a copy of Southern Politics, published many years ago, but considered by many to still be an authoritative look at the subject, so much so that it was reissued thirty years after its initial publication.

For anyone puzzled by the person in >24 SassyLassy: above, she is Ultra Violet, real name Isabelle Collin Dufresne, one of Andy Warhol's superstars.

Your review does make me more hopeful about reading it. I'm not sure what the hesitation is. I read it in my early teens and thought it was a great adventure. For the past few years, I've thought it could do with a rereading but now it seems fraught with so much literary baggage. Maybe it's better not to know these things when we read.

>27 mabith: My first step has been ordering a copy of Southern Politics, published many years ago, but considered by many to still be an authoritative look at the subject, so much so that it was reissued thirty years after its initial publication.

For anyone puzzled by the person in >24 SassyLassy: above, she is Ultra Violet, real name Isabelle Collin Dufresne, one of Andy Warhol's superstars.

29SassyLassy

2. Winter by Christopher Nicholson

first published 2014

finished reading January 3, 2018

Thomas Hardy was completely infatuated. He pondered whether he was in love. He went further and wondered whether the feeling was returned. He mentioned it to no one. Thomas Hardy was eighty-four. Gertrude Bugler was twenty-six. Mrs Hardy was forty-six and not at all pleased.

Christopher Nicholson has taken these three people and created a fictionalized look at actual events. The Hardys were living at Max Gate, the home Hardy had built for his first wife Emma. The second Mrs Hardy, Florence, loathed the place. She felt it made her physically ill. The trees that Hardy had planted were now full grown. Florence believed that spores from the trees caused cancer. Thomas believed the trees would feel the pain of being cut down, effectively murdered, and refused to do anything. They were a major cause of contention.

Then one day, it occurred to Florence that preparations for the upcoming local stage production of Tess of the D'Urbervilles were entirely too focussed on Gertrude Bugler. Gertrude was to play Tess. Years earlier Thomas had seen Gertrude's mother and based his description of Tess on her. Now he believed Gertrude was the only person to play Tess, right down to her perfect "Wessex" accent. The play went ahead and Gertrude was engaged to play the role in the upcoming London production.

Florence put down her foot. Thomas fought back. Florence found poems Thomas had written about Gertrude. Not able to tell Thomas she had found them, she intensified the battle of the trees instead.

Nicholson uses the third person narrator to tell Hardy's part of the story. Florence's side is told in the first person. Gertrude tells what little she knows of her part in it all. Nicholson does an excellent job of portraying Hardy's intransigence, Florence's rising hysteria, and Gertrude's confusion. He also explores other aspects of their personalities, especially that of Hardy as he contemplated death and his legacy. There was Hardy in the churchyard envisioning his own funeral, counting up who would attend.

...and who was that? Barrie! He was pleased by that; excellent that Barrie had bothered to come down, the old fox. There was Augustus John looking his usual angry self, glaring at the universe. O, and Kipling, too, with a fat moustache, even fatter than Barrie's.

He also thought of how he would be remembered and what they would say of him. He knew his novels would survive for awhile, but worried about his poetry.

He was a famous man; his death would have been reported in every newspaper, with long obituary notices and lavish tributes. Would any record the struggles of his early years?... Would any say how much doubt and uncertainty had dogged his footsteps, and how much determination and perseverance had been necessary to achieve what he had achieved? No, they would not say anything of the sort. How little they knew! And quite right, too: there was no need for them to know everything.

Winter is tinged with the sorrow of both Florence and Thomas realizing the increasing barrenness of their lives. Hardy's poetry has failed him. Florence is now past child bearing and is facing years on her own. All in all, this was an excellent, if sombre portrayal of two people locked in a mismatched marriage, and of the writer in winter.

30tonikat

>28 SassyLassy: ahhh I seee. I’m not very good at this am I.

31baswood

Excellent review of Winter, Christopher Nicholson. Fictionalized histories can be entertaining as long as they don't stray too far from your own pictures of the authors. Even better if they make you go back and read some more Hardy.

32thorold

>29 SassyLassy: Interesting. Sounds like something else I'll have to put on my list now that I've uncorked the Hardy bottle again... But first I need to re-read a bit more of the man himself.

33valkyrdeath

I'm still catching up with everyone's threads, so dropping by to keep track of your thread. Hope you have a good year of reading ahead. It seems like you've made a good start already!

34janeajones

Intriguing review of Winter. I'll keep an eye out for it.

35SassyLassy

This next book would be in the uncharted waters category; an author new to me, Magda Szabó, but one whom I have seen positively reviewed in past CR years.

3. Katalin Street by Magda Szabó translated from the Hungarian by Len Rix, 2017

first published as Katalin Utca in 1969

finished reading January 9, 2018

Some believe that those who die suddenly and unexpectedly stay in their temporal world in spirit form until they are reconciled to death, or until those they are watching over join them. The dead though, don't age, while those left behind do; aging inevitably, sometimes dying inside of shame, of grief, of loss of hope. So it was on Katalin Street, where an alert lively girl first watched those she had considered her family grow up, grow old, and alter irrevocably.

In pre WWII Budapest, there were three particular houses facing the river. The sisters Blanka and Irén lived in one, Henriette in another, and a slightly older boy, Bálint, in the third. The children played together, their parents were friends, and the families celebrated small occasions together throughout the year. The three girls all loved Bálint, whose name means Valentine, each in her own way.

If this were a straightforward chronological narrative, the novel would start here. Instead, it starts with Irén, her family, and Bálint on the other side of the river, in Soviet era housing, looking back at their old home. None of them had ever got used to the apartment or grown to like it. They just put up with it, as with so many other things. Although they rarely spoke of it with each other, they all yearned to return to their old homes on Katalin Street, and even more, to return to the people they had been. Henriette, now dead, knew that you can't go back without those who have since died. The past cannot be recreated.

Time can be fluid in our thoughts though. Szabó's book moves back and forth from the 1930s right up to 1968. Nazis come and go to be replaced by the Soviets. People go, but don't always come back: dead or exiled. Even in sections of the book with a date as heading, some characters are in one year, while at the same time others are in another.

What Szabó is telling the reader is a stark message about what we do to each other and what life does to us:

For those left behind, There came too the realization that advancing age had taken the past. ... They had discovered too that the difference between the living and the dead is merely qualitative, that it doesn't count for much.

The penultimate sentence of the novel, In everyone's life there is only one person whose name can be cried out in the moment of death, sent me back to the beginning, and an immediate reread, for now the use of that same sentence, first seen early in the novel, gave a different focus and I wanted to follow that path. There are many paths in this book though, and a different one could be taken with each reading. This is the first book I have read by Szabó, but it won't be the last.

------------

edited for numbers as it appears I can't count to 3

3. Katalin Street by Magda Szabó translated from the Hungarian by Len Rix, 2017

first published as Katalin Utca in 1969

finished reading January 9, 2018

Some believe that those who die suddenly and unexpectedly stay in their temporal world in spirit form until they are reconciled to death, or until those they are watching over join them. The dead though, don't age, while those left behind do; aging inevitably, sometimes dying inside of shame, of grief, of loss of hope. So it was on Katalin Street, where an alert lively girl first watched those she had considered her family grow up, grow old, and alter irrevocably.

In pre WWII Budapest, there were three particular houses facing the river. The sisters Blanka and Irén lived in one, Henriette in another, and a slightly older boy, Bálint, in the third. The children played together, their parents were friends, and the families celebrated small occasions together throughout the year. The three girls all loved Bálint, whose name means Valentine, each in her own way.

If this were a straightforward chronological narrative, the novel would start here. Instead, it starts with Irén, her family, and Bálint on the other side of the river, in Soviet era housing, looking back at their old home. None of them had ever got used to the apartment or grown to like it. They just put up with it, as with so many other things. Although they rarely spoke of it with each other, they all yearned to return to their old homes on Katalin Street, and even more, to return to the people they had been. Henriette, now dead, knew that you can't go back without those who have since died. The past cannot be recreated.

Time can be fluid in our thoughts though. Szabó's book moves back and forth from the 1930s right up to 1968. Nazis come and go to be replaced by the Soviets. People go, but don't always come back: dead or exiled. Even in sections of the book with a date as heading, some characters are in one year, while at the same time others are in another.

What Szabó is telling the reader is a stark message about what we do to each other and what life does to us:

...the most frightening thing of all about the loss of youth is not what is taken away, but what is granted in exchange. Not wisdom. Not sound judgement or tranquillity. Only the awareness of universal disintegration.

For those left behind, There came too the realization that advancing age had taken the past. ... They had discovered too that the difference between the living and the dead is merely qualitative, that it doesn't count for much.

The penultimate sentence of the novel, In everyone's life there is only one person whose name can be cried out in the moment of death, sent me back to the beginning, and an immediate reread, for now the use of that same sentence, first seen early in the novel, gave a different focus and I wanted to follow that path. There are many paths in this book though, and a different one could be taken with each reading. This is the first book I have read by Szabó, but it won't be the last.

------------

edited for numbers as it appears I can't count to 3

36SassyLassy

>31 baswood: >32 thorold: More Hardy reading is definitely in order.

37japaul22

>35 SassyLassy: excellent review. I read The Door recently and found it intriguing though I felt my lack of knowledge of her culture kept me from the full meaning of her novel. Really great writing, though. I’ll look for this.

38mabith

I put Magda Szabo on my to-read list after seeing a number of glowing CR reviews too, and glad to add another to that pile!

39baswood

Great review of Katalin Street. An author new to me.

the most frightening thing of all about the loss of youth is not what is taken away, but what is granted in exchange. Not wisdom. Not sound judgement or tranquillity. Only the awareness of universal disintegration.

That is a stark message

the most frightening thing of all about the loss of youth is not what is taken away, but what is granted in exchange. Not wisdom. Not sound judgement or tranquillity. Only the awareness of universal disintegration.

That is a stark message

40auntmarge64

>35 SassyLassy: What a lovely review and wonderful-sounding book. Going on the TBR list for sure, and my library even has an e-copy.

42chlorine

I enjoyed your reviews and am looking forward to the ones that will follow this year, especially the Zola ones! I'm currently reading The belly of Paris myself.

I read The door by Szabo and did not quite know what to make of it. On some level I rather liked it, but I feel as if something has eluded me.

I read The door by Szabo and did not quite know what to make of it. On some level I rather liked it, but I feel as if something has eluded me.

43rachbxl

Another one here who read The Door and was left feeling I'd missed something. I know several people who read it in Hungarian and loved it; I suspect that the problem is not the translation, but, as japaul says, not knowing enough about Hungarian culture. I very much liked the writing, though, and would happily give Szabo another chance; Katalin Street has gone on my wishlist.

44janeajones

OOh - Katalin Street is next on my wish list -- or Amazon ordering list.

45Caroline_McElwee

>35 SassyLassy: I read The Door too and thought it excellent, so adding this to the list Sassy.

46SassyLassy

You've all convinced me I must read The Door! Up next on the order list.

>42 chlorine: I'm currently waiting patiently for my next Zola to arrive. It's well overdue. Did you know that Oxford released at least two new translations in 2017?

>39 baswood: Stark indeed, but then that is the kind of book I like, sort of like reading Lessing!

>42 chlorine: I'm currently waiting patiently for my next Zola to arrive. It's well overdue. Did you know that Oxford released at least two new translations in 2017?

>39 baswood: Stark indeed, but then that is the kind of book I like, sort of like reading Lessing!

47SassyLassy

This book was not what I expected, but then I didn't see the subtitle until I sat down to read it. Fascinating all the same.

I had found the book unread in a seaside used bookstore, only open after about 22:00 hours, a time which varied with the proprietor's whims, and usually long after the town had gone to bed.

4. Winter Sea: War, Journeys, Writers by Alan Ross

first published 1997

finished reading January 14, 2018

Winter Sea is a diary of sorts of a 1997 trip across the Gulf of Finland and through parts of the Baltic and North Seas. Yet as the subtitle, "War, Journeys, Writers" suggests, it is also musings on all three during these travels. Even more, it is a writer approaching the winter of his life and thinking back.

Alan Ross had left Oxford to serve in WWII. He was part of the Royal Navy convoys to Murmansk and Archangel; missions with a disastrous death rate. At the end of the war, he accompanied German ships being returned to their ports of origin now under Allied control. One such voyage took him just of the coast of Tallinn, where the German ship was handed over to the Soviets. The nominal command was Korvetten Kapitan Richard Schlemmer.

Fast forward to 1997, and Ross sailing across the Gulf of Finland from Helsinki to Tallinn, and then travelling by land to Haapsalu. Memories of Schlemmer feature largely as the two had become friends in the years following the war. Schlemmer, now dead, had moved to Estonia later in life, and had hoped to have Ross visit him there. In a sense, this trip was that visit.

Ross was also a small craft pleasure sailor. No such person can contemplate Estonian waters without bringing to mind Arthur Ransome. Ransome's adventures and misadventures with three boats off the coast were the subject of several books, now quite rare. Ross was rereading these on his trip. Ransome played several roles during WWI. Ross, citing a former Foreign Minister, credits him with being in part responsible for Estonian independence between the two world wars.

This part of the book was perhaps the most interesting. Ross ruminates on the Estonian experiences of Jaan Kross, Graham Greene, Colin Thubron, and the Baroness Moura Budberg, mistress of Gorky, Bruce Lockhart and H G Wells. A noted poet himself, Ross quotes the Estonian poet Jaan Kaplinski

Oslo to Bergen by train is the source of the next segment. Tales of naval battles off Norway mix with a long reflection on Knut Hamsun's semi-autobiographical Hunger, and the political fortunes of Hamsun himself. Ross walks the streets of Oslo following in the steps of the protagonist in much the same way Joyce lovers walk Dublin. He quotes I B Singer comparing the hero of Hunger to Raskolnikov. The poetry in this section is that of Nordahl Grieg, put into English equivalent by Ross.

During the late summer of 1945, Ross was stationed in Buxtehude. There he read most of Ernest Junger's works in German. Apart from his name, this author was unfamiliar to me, and his writing as recounted by Ross, especially Auf den Marmorklippen seem unlikely to be anything I would find myself looking for in translation. While his other discussions of authors and books had made me want to read and reread them, this made this small segment of the book less interesting for me.

The final excursion was a true trip down Memory Lane for Ross: Hamburg to Wilhelmshaven in January, the coldest in decades. Here the journey ends with a sea that can no longer be seen, with ice reaching to the horizon... the sea itself invisible. He had returned to his White Sea, the sea of Archangel

______________

photo from The Guardian

Alan Ross had a wide range of interests and a life which managed to accommodate them:

https://www.theguardian.com/news/2001/feb/16/guardianobituaries.books

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2006/jan/28/featuresreviews.guardianreview29

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2009/nov/21/william-boyd-hero-alan-ross

I had found the book unread in a seaside used bookstore, only open after about 22:00 hours, a time which varied with the proprietor's whims, and usually long after the town had gone to bed.

4. Winter Sea: War, Journeys, Writers by Alan Ross

first published 1997

finished reading January 14, 2018

Winter Sea is a diary of sorts of a 1997 trip across the Gulf of Finland and through parts of the Baltic and North Seas. Yet as the subtitle, "War, Journeys, Writers" suggests, it is also musings on all three during these travels. Even more, it is a writer approaching the winter of his life and thinking back.

Alan Ross had left Oxford to serve in WWII. He was part of the Royal Navy convoys to Murmansk and Archangel; missions with a disastrous death rate. At the end of the war, he accompanied German ships being returned to their ports of origin now under Allied control. One such voyage took him just of the coast of Tallinn, where the German ship was handed over to the Soviets. The nominal command was Korvetten Kapitan Richard Schlemmer.

Fast forward to 1997, and Ross sailing across the Gulf of Finland from Helsinki to Tallinn, and then travelling by land to Haapsalu. Memories of Schlemmer feature largely as the two had become friends in the years following the war. Schlemmer, now dead, had moved to Estonia later in life, and had hoped to have Ross visit him there. In a sense, this trip was that visit.

Ross was also a small craft pleasure sailor. No such person can contemplate Estonian waters without bringing to mind Arthur Ransome. Ransome's adventures and misadventures with three boats off the coast were the subject of several books, now quite rare. Ross was rereading these on his trip. Ransome played several roles during WWI. Ross, citing a former Foreign Minister, credits him with being in part responsible for Estonian independence between the two world wars.

This part of the book was perhaps the most interesting. Ross ruminates on the Estonian experiences of Jaan Kross, Graham Greene, Colin Thubron, and the Baroness Moura Budberg, mistress of Gorky, Bruce Lockhart and H G Wells. A noted poet himself, Ross quotes the Estonian poet Jaan Kaplinski

The East-West border is always wandering,

sometimes eastward, sometimes west,

and we do not know exactly where it is just now:

in Guagamela, in the Urals, or maybe in ourselves.

Oslo to Bergen by train is the source of the next segment. Tales of naval battles off Norway mix with a long reflection on Knut Hamsun's semi-autobiographical Hunger, and the political fortunes of Hamsun himself. Ross walks the streets of Oslo following in the steps of the protagonist in much the same way Joyce lovers walk Dublin. He quotes I B Singer comparing the hero of Hunger to Raskolnikov. The poetry in this section is that of Nordahl Grieg, put into English equivalent by Ross.

During the late summer of 1945, Ross was stationed in Buxtehude. There he read most of Ernest Junger's works in German. Apart from his name, this author was unfamiliar to me, and his writing as recounted by Ross, especially Auf den Marmorklippen seem unlikely to be anything I would find myself looking for in translation. While his other discussions of authors and books had made me want to read and reread them, this made this small segment of the book less interesting for me.

The final excursion was a true trip down Memory Lane for Ross: Hamburg to Wilhelmshaven in January, the coldest in decades. Here the journey ends with a sea that can no longer be seen, with ice reaching to the horizon... the sea itself invisible. He had returned to his White Sea, the sea of Archangel

White sea of memory, of fear and adventure, of camaraderie and consolation. White sea of the unknown, on which nothing and everything is written.

______________

photo from The Guardian

Alan Ross had a wide range of interests and a life which managed to accommodate them:

https://www.theguardian.com/news/2001/feb/16/guardianobituaries.books

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2006/jan/28/featuresreviews.guardianreview29

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2009/nov/21/william-boyd-hero-alan-ross

48.Monkey.

>47 SassyLassy: That sounds quite interesting.

49janeajones

47> Intriguing review. Sounds rather poetic.

50chlorine

>46 SassyLassy: I'm actually French so I'm lucky to be able to read Zola in the original text and not worry about translations. :)

One thing that puzzles me in the Zolas I've read recently: what's up with men pinching women they want to have sex with?! I can't really understand whether it's supposed to be pleasurable for the woman or if it's a sign of domination...

Very nice review of the Ross book.

One thing that puzzles me in the Zolas I've read recently: what's up with men pinching women they want to have sex with?! I can't really understand whether it's supposed to be pleasurable for the woman or if it's a sign of domination...

Very nice review of the Ross book.

51thorold

>47 SassyLassy: I think you’ve just put another item on my TBR list! That bookshop sounds fun, too.

Have you read the Ransome books? I’ve been vaguely on the lookout for them for years but never seen them anywhere.

Have you read the Ransome books? I’ve been vaguely on the lookout for them for years but never seen them anywhere.

53SassyLassy

>50 chlorine: Blushing, of course you are reading in French! Are they the Mitterand editions?

Perhaps pinching was a Zola thing?

>51 thorold: Although I look for the Ransome books in every semi-nautical bookshop or section of a bookshop I enter, I have not found any. The originals are available online for a lot of money. Now that some have been reissued lately, with sketches by Ransome, I will probably go that route. Naturally I have read all the books for children: Swallows and Amazons forever!

I love these kind of bookshops.

>52 baswood: I remember London Magazine, now The London Magazine once more. I hadn't connected Ross as the editor until I read the end flap of the book, and then all those author connections made so much more sense.

>49 janeajones: It was poetic even in prose. Ross wrote many other books, on a variety of subjects from cricket to travel to his own poetry. They must be out there somewhere, but I was surprised to see only five other people on LT have this particular book.

>48 .Monkey.: It was interesting indeed and confirmed me in one of my greatest travel dreams, which is to go by ferry around these northern seas and to cross from Oslo to Bergen by train. Not sure about the winter part though, as I have had my fair share of it in Canada.

----

edited for spelling

Perhaps pinching was a Zola thing?

>51 thorold: Although I look for the Ransome books in every semi-nautical bookshop or section of a bookshop I enter, I have not found any. The originals are available online for a lot of money. Now that some have been reissued lately, with sketches by Ransome, I will probably go that route. Naturally I have read all the books for children: Swallows and Amazons forever!

I love these kind of bookshops.

>52 baswood: I remember London Magazine, now The London Magazine once more. I hadn't connected Ross as the editor until I read the end flap of the book, and then all those author connections made so much more sense.

>49 janeajones: It was poetic even in prose. Ross wrote many other books, on a variety of subjects from cricket to travel to his own poetry. They must be out there somewhere, but I was surprised to see only five other people on LT have this particular book.

>48 .Monkey.: It was interesting indeed and confirmed me in one of my greatest travel dreams, which is to go by ferry around these northern seas and to cross from Oslo to Bergen by train. Not sure about the winter part though, as I have had my fair share of it in Canada.

----

edited for spelling

54chlorine

>53 SassyLassy: Don't blush about not remembering my nationality, I think it's really hard to keep track of who comes from where!

I have an e-reader so I got free ebook copies from the website Ebooks libres et gratuits.

I think it would maybe be nice to have an edition with notes instead but I value so much the fact that so many public domain books are available for free that I'm quite happy with the raw text (even if there are a few errors that have been introduced by the scanning process).

I have an e-reader so I got free ebook copies from the website Ebooks libres et gratuits.

I think it would maybe be nice to have an edition with notes instead but I value so much the fact that so many public domain books are available for free that I'm quite happy with the raw text (even if there are a few errors that have been introduced by the scanning process).

55wandering_star

>47 SassyLassy: I love the sound of your midnight bookshop!

56labfs39

Oh, my. I finally found time to read your thread; when I get behind, I know it will take a while, because your reviews are so good!

>29 SassyLassy: Your review makes this novel very enticing, but I have a hard time reading fiction about real people. I think to myself, why don't I just read the (auto)biography! But you make me think that there is something more that I would get from Winter.

>35 SassyLassy: Another wonderful review of an author that I too have been wanting to read. DieF recommended The Door years ago, but I think I might start here instead. Fluidity of boundaries in East European is of particular interest to me.

>47 SassyLassy: Wow. So much contained within 150 pages! Thank you for giving us a thorough taste (yes, an oxymoron, but I hope you know what I mean). Ross sounds like a fascinating character, and although I have Ransome's children's books, I had no idea about the other facets of his life. Hunger was an interesting, if depressing read. Its similarity to Crime and Punishment made me wonder whether Hamsun was trying to write the same novel for Norway. I still haven't read Storm of Steel, although it's been on my to-read-sooner-rather-than-later table for two years now! I am bookmarking your post so that I can follow your links. So much to explore in your post! A deluge of book bullets (another oxymoron).

Oh, and hello!

>29 SassyLassy: Your review makes this novel very enticing, but I have a hard time reading fiction about real people. I think to myself, why don't I just read the (auto)biography! But you make me think that there is something more that I would get from Winter.

>35 SassyLassy: Another wonderful review of an author that I too have been wanting to read. DieF recommended The Door years ago, but I think I might start here instead. Fluidity of boundaries in East European is of particular interest to me.

>47 SassyLassy: Wow. So much contained within 150 pages! Thank you for giving us a thorough taste (yes, an oxymoron, but I hope you know what I mean). Ross sounds like a fascinating character, and although I have Ransome's children's books, I had no idea about the other facets of his life. Hunger was an interesting, if depressing read. Its similarity to Crime and Punishment made me wonder whether Hamsun was trying to write the same novel for Norway. I still haven't read Storm of Steel, although it's been on my to-read-sooner-rather-than-later table for two years now! I am bookmarking your post so that I can follow your links. So much to explore in your post! A deluge of book bullets (another oxymoron).

Oh, and hello!

57Caroline_McElwee

>47 SassyLassy: Fascinating Sassy. Love the sound effects f the bookshop too. I love when I’m in Paris, that Shakespeare and Co is open til late.

59mabith

Winter Sea sounds fascinating.

60SassyLassy

This is a book I read last year. I have just posted this review on my 2017 thread, but since most of us have moved on to 2018, I have also posted it here, as I only got around to this review yesterday. Also my next Zola will be 10 in the suggested reading order, so it naturally follows from this one. I won't count this for my 2018 totals.

_____________

Life seemed to be getting back to normal by early October, after a crazy year. It was time to start reading Zola again, last visited in April. My reading of the full Rougon Macquart series was hampered by only reading those in English translation, and of those, only recent translations. I did not want bowdlerized versions. When I started the series in January 2016, these restrictions meant that of the twenty novels, I would be skipping 2, 9, 10 and 20 in the suggested reading order. I thought I was now at 18, but a quick check revealed two more translations had been released in 2017, so I happily went back to 9, The Sin of Abbé Mouret.

The Sin of Abbé Mouret translated from the French by Valerie Minogue 2017

first published as La Faute de Abbé Mouret in 1875

finished reading October 25, 2017

The Sin of Abbé Mouret starts out in almost wooden fashion, reminiscent of The Crime of Father Amaro, published the same year. Serge Mouret was a young priest, fresh out of the seminary. Prayer and devotion meant so much to him that he found it almost impossible to imagine the struggles other priests might have with their less spiritual sides. However, this is Zola, and the themes and descriptions soon let the reader know it.

Serge was a product of both the Rougons and Macquarts. His mother was from the respectable Rougon side of the family, and his father from the tainted Macquart side. Since Zola's aim was to study family, heredity and environment, we know that such a lineage will be fraught with tension and turmoil. Furthermore, not only was Serge's father committed to an asylum, perhaps expected as a Macquart, Serge's mother could be seen as suffering from mental instability at the end of The Conquest of Plassans, when she fell under the influence of the terrifying Abbé Faujas.

Serge had not only renounced the world of the flesh when he took his priestly vows, he also renounced the material world. He was now living in Les Artaud with a housekeeper and his mentally deficient younger sister Désirée. He had given his money to his much more worldly older brother Octave, from Pot Luck and The Ladies' Paradise. Les Artaud was not the place to be though for a man who found such disturbance in what he considered to be carnal sins. The villagers were all related, were wildly promiscuous, and barely paid lip service to the rites of the Catholic Church, a religion Zola shows as completely unable to meet their needs. Nature also showed no respect. Chickens pecked on the stone floor of the church, birds flew through the broken windows, a rowan tree thrust its branches in. At the altar, the priest, lost in his devotions, ... did not even hear this invasion of the nave by the warm May morning, or the rising flood of sunshine, greenery, and birds, which overflowed even up to the foot of Calvary, on which nature, dammed, lay dying. Nature was already fighting him.

Just outside the village, was a magic estate, Paradou. It had been abandoned a century before. Built in the time of Louis XV, it was like a little Versailles. But the lady of the Paradou must have died there, for she was never seen again after the first season. The following year, the chateau burned down, the park gates were nailed up, and even the narrow slits in the wall filled up with earth, so ever since that distant era, no eye had penetrated the vast enclosure which occupied the whole of one of the high plateaux of the Garrigues. Nature there was left to run riot.

The place was looked after by the caretaker Jeanbernat, the Philosopher, who took care to lodge outside the walls. His sixteen year old niece lived with him. Serge first went to Paradou with his uncle Dr Pascal, the family recorder, to visit Jeanbernat who was rumoured to be dying. Jeanbernat represents the rationalists and the voice of reason against dogma, and as such felt no reticence in challenging Serge on his beliefs. It was here that the Abbé caught his first glimpse of Albine, This blonde child, with her long face, aflame with life, seemed to him to be the mysterious and disturbing daughter of that forest he had glimpsed in a patch of light when he first arrived.

Since the age of five, Serge had been devoted to the Virgin Mary, so white, so pure. He thought of her as a divine sister, the two of them innocents in a sinful world. His priestly devotions had continued that marian focus. Mary was the only representation of the divine to grace his cell; Mary, the ever pure, in an image of the Immaculate Conception. Now, suddenly, he could not help seeing her with the eyes of an adolescent. He feared to contaminate her with his impure thoughts as her image became confused with that of Albine. Feverish, rambling, he prayed.

Here the book shifts. Serge awoke in a strange room, festooned with fading images of cherubs. Albine was his nurse. He had been there some time. As he convalesced, Albine coaxed him outdoors into the gardens of the Paradou. Gradually the two innocents explored her paradise together in Zola's version of the Garden of Eden. The horticulturalist might quibble that the combinations of blooms Zola gathers don't occur in the real world, but this is the Garden, where all things are possible. There are pages and pages of incredibly lush descriptions of the animals, trees and flowers, done with incredible and accurate detail, everything with voluptuous overtones:

However, just as in the original Garden, there is a forbidden tree and there is a fall. Serge, whose illness had resulted in his forgetting his priestly life, suddenly recalled it, and was driven from the garden. The clash of religion and reality resumed, for Serge and internal one, for Zola an eternal one.

___________________

One thing I did wonder about was the translation of the title, in French La Faute de Abbé Mouret which to me is more a fault or an error, both of which fit here, than an actual sin. Of course, as the English title indicates, Mouret does commit a sin in the eyes of the Church, but I would think of that as le péché, not une faute. Could some francophone please help me out here?

_____________

Life seemed to be getting back to normal by early October, after a crazy year. It was time to start reading Zola again, last visited in April. My reading of the full Rougon Macquart series was hampered by only reading those in English translation, and of those, only recent translations. I did not want bowdlerized versions. When I started the series in January 2016, these restrictions meant that of the twenty novels, I would be skipping 2, 9, 10 and 20 in the suggested reading order. I thought I was now at 18, but a quick check revealed two more translations had been released in 2017, so I happily went back to 9, The Sin of Abbé Mouret.

The Sin of Abbé Mouret translated from the French by Valerie Minogue 2017

first published as La Faute de Abbé Mouret in 1875

finished reading October 25, 2017

The Sin of Abbé Mouret starts out in almost wooden fashion, reminiscent of The Crime of Father Amaro, published the same year. Serge Mouret was a young priest, fresh out of the seminary. Prayer and devotion meant so much to him that he found it almost impossible to imagine the struggles other priests might have with their less spiritual sides. However, this is Zola, and the themes and descriptions soon let the reader know it.

Serge was a product of both the Rougons and Macquarts. His mother was from the respectable Rougon side of the family, and his father from the tainted Macquart side. Since Zola's aim was to study family, heredity and environment, we know that such a lineage will be fraught with tension and turmoil. Furthermore, not only was Serge's father committed to an asylum, perhaps expected as a Macquart, Serge's mother could be seen as suffering from mental instability at the end of The Conquest of Plassans, when she fell under the influence of the terrifying Abbé Faujas.

Serge had not only renounced the world of the flesh when he took his priestly vows, he also renounced the material world. He was now living in Les Artaud with a housekeeper and his mentally deficient younger sister Désirée. He had given his money to his much more worldly older brother Octave, from Pot Luck and The Ladies' Paradise. Les Artaud was not the place to be though for a man who found such disturbance in what he considered to be carnal sins. The villagers were all related, were wildly promiscuous, and barely paid lip service to the rites of the Catholic Church, a religion Zola shows as completely unable to meet their needs. Nature also showed no respect. Chickens pecked on the stone floor of the church, birds flew through the broken windows, a rowan tree thrust its branches in. At the altar, the priest, lost in his devotions, ... did not even hear this invasion of the nave by the warm May morning, or the rising flood of sunshine, greenery, and birds, which overflowed even up to the foot of Calvary, on which nature, dammed, lay dying. Nature was already fighting him.

Just outside the village, was a magic estate, Paradou. It had been abandoned a century before. Built in the time of Louis XV, it was like a little Versailles. But the lady of the Paradou must have died there, for she was never seen again after the first season. The following year, the chateau burned down, the park gates were nailed up, and even the narrow slits in the wall filled up with earth, so ever since that distant era, no eye had penetrated the vast enclosure which occupied the whole of one of the high plateaux of the Garrigues. Nature there was left to run riot.

The place was looked after by the caretaker Jeanbernat, the Philosopher, who took care to lodge outside the walls. His sixteen year old niece lived with him. Serge first went to Paradou with his uncle Dr Pascal, the family recorder, to visit Jeanbernat who was rumoured to be dying. Jeanbernat represents the rationalists and the voice of reason against dogma, and as such felt no reticence in challenging Serge on his beliefs. It was here that the Abbé caught his first glimpse of Albine, This blonde child, with her long face, aflame with life, seemed to him to be the mysterious and disturbing daughter of that forest he had glimpsed in a patch of light when he first arrived.

Since the age of five, Serge had been devoted to the Virgin Mary, so white, so pure. He thought of her as a divine sister, the two of them innocents in a sinful world. His priestly devotions had continued that marian focus. Mary was the only representation of the divine to grace his cell; Mary, the ever pure, in an image of the Immaculate Conception. Now, suddenly, he could not help seeing her with the eyes of an adolescent. He feared to contaminate her with his impure thoughts as her image became confused with that of Albine. Feverish, rambling, he prayed.

O Mary, Chosen Vessel, castrate in me all humanity, make me a eunuch among men, so you may without fear grant me the treasure of your virginity!

And Abbé Mouret, his teeth chattering, collapsed on the tiled floor, struck down by fever.

Here the book shifts. Serge awoke in a strange room, festooned with fading images of cherubs. Albine was his nurse. He had been there some time. As he convalesced, Albine coaxed him outdoors into the gardens of the Paradou. Gradually the two innocents explored her paradise together in Zola's version of the Garden of Eden. The horticulturalist might quibble that the combinations of blooms Zola gathers don't occur in the real world, but this is the Garden, where all things are possible. There are pages and pages of incredibly lush descriptions of the animals, trees and flowers, done with incredible and accurate detail, everything with voluptuous overtones:

The living flowers opened out like naked flesh, like bodices revealing the treasures of the bosom. There were yellow roses like petals from the golden skin of barbarian maidens, roses the colour of straw, lemon-coloured roses, and some the colour of the sun, all the varying shades of skin bronzed by ardent skies. Then the bodies grew softer, the tea roses becoming delightfully moist and cool, revealing what modesty had hidden, parts of the body not normally shown, fine as silk and threaded with a blue network of veins.

However, just as in the original Garden, there is a forbidden tree and there is a fall. Serge, whose illness had resulted in his forgetting his priestly life, suddenly recalled it, and was driven from the garden. The clash of religion and reality resumed, for Serge and internal one, for Zola an eternal one.

___________________

One thing I did wonder about was the translation of the title, in French La Faute de Abbé Mouret which to me is more a fault or an error, both of which fit here, than an actual sin. Of course, as the English title indicates, Mouret does commit a sin in the eyes of the Church, but I would think of that as le péché, not une faute. Could some francophone please help me out here?

61thorold

Faute has both religious and secular implications - it can be a synonym of péché, and it’s definitely used in religious language in that way, but it also has the general sense of violating a moral rule, and the particular sense of extramarital relations and their consequences (l’enfant d’une faute, etc.). I don’t think that English can do all that with one word, so “sin” is probably the best way of getting it across.

cf. the TLF here: http://stella.atilf.fr/Dendien/scripts/tlfiv5/visusel.exe?12;s=16759365;r=1;nat=...;

I think I must have fainted several times trying to get through that garden when I first read it - amazing how steamy he can make it without a greenhouse ...

cf. the TLF here: http://stella.atilf.fr/Dendien/scripts/tlfiv5/visusel.exe?12;s=16759365;r=1;nat=...;

I think I must have fainted several times trying to get through that garden when I first read it - amazing how steamy he can make it without a greenhouse ...

62baswood

Great review of The sin of Abbé Mouret it sounds typical Zola. You are getting close now to completing the whole series.

63chlorine

What thorold said concerning faute.

Great review of this Zola. I tried to read it many years ago and I remember that I was bored with it and did not finish it, and this was at a time when I quit on a book much more seldom than now.

Therefore I'm a little apprehensive of it now. But anyway I have La conquête de Plassans to read before this one!

Great review of this Zola. I tried to read it many years ago and I remember that I was bored with it and did not finish it, and this was at a time when I quit on a book much more seldom than now.

Therefore I'm a little apprehensive of it now. But anyway I have La conquête de Plassans to read before this one!

64arubabookwoman

>60 SassyLassy: I found The Sin of Abbe Mouret to be the strangest Rougon-Macquart I've read so far. I thought it verged on magical realism.

I stalled on my Rougon-Macquart journey several years ago about half-way through (The Masterpiece). I really have to get back to it.

I stalled on my Rougon-Macquart journey several years ago about half-way through (The Masterpiece). I really have to get back to it.

65SassyLassy

>61 thorold: >63 chlorine: Thanks for the explanations. I am getting the message "session expirée" but I will go with this as another word without a direct equivalent, like l'assommoir, which seems to generate discussion. I have not found my French - English dictionary since I moved, nor my English dictionaries for that matter. The box marked "reference" yielded useful books, but no dictionaries other than Esperanto and Scots.

>61 thorold: "amazing how steamy he can make it without a greenhouse ..." too funny!

>62 baswood: Only three more left in English translation, then I may have to tackle the final two in French!

>64 arubabookwoman: I thought that about magical realism too at times. Have you read The Dream? I had the same sense there.

Interesting about The Masterpiece. It's odd where we each stall. Mine was The Ladies' Paradise, which is one that many recommend as a start, but those floors and floors of merchandise would have had me running for the exits in no time in real life, and so the feeling was as I read the book. I kept going though. I noticed that in her review of The Sin of Abbé Mouret, rebecca said she wouldn't have finished it if it hadn't been Zola, so that one would be a stall in her case as with chlorine above.

>61 thorold: "amazing how steamy he can make it without a greenhouse ..." too funny!

>62 baswood: Only three more left in English translation, then I may have to tackle the final two in French!

>64 arubabookwoman: I thought that about magical realism too at times. Have you read The Dream? I had the same sense there.

Interesting about The Masterpiece. It's odd where we each stall. Mine was The Ladies' Paradise, which is one that many recommend as a start, but those floors and floors of merchandise would have had me running for the exits in no time in real life, and so the feeling was as I read the book. I kept going though. I noticed that in her review of The Sin of Abbé Mouret, rebecca said she wouldn't have finished it if it hadn't been Zola, so that one would be a stall in her case as with chlorine above.

66thorold

>65 SassyLassy: Sorry, obviously not a portable link. But the TLF is a useful resource if you want some more detail on a French word than what your desk dictionary gives you. Try going to http://stella.atilf.fr , click on the big “Entrer...” button, and enter the word “faute” top right.

67SassyLassy

>66 thorold: That link worked- thanks - what a great resource. I think I liked the J'ai péché par ma très grande faute in version 9 for this particular book, so it now the translation works for me. I should never question the translators, but now I have a new sense of the word.

68SassyLassy

This year's reading so far had been somewhat sombre. It was time for some derring-do, so I turned to my triumvirate of adventure writers and came up with this, on the TBR pile since August 21st, 2013.

5. La Reine Margot by Alexandre Dumas translated from the French by David Bogue, 1846, "modernized and revised against the standard French text" of La Reine Margot, ed Claude Schopp, by David Coward

first published in serial form in La Presse from December 25, 1844 to April 5, 1845

finished reading January 24, 2018

The works of Alexandre Dumas are known for many things: adventure, romance, beautiful women, dastardly evil- doers. Accurate history is not one of his fortes. Dumas loved to take figures from history, imbue them with legendary characteristics, and toss them into a stew of fact and fiction. La Reine Margot is a perfect example.

The novel starts with two historic events. The first was the 1572 wedding of Marguerite de Valois, Catholic daughter of Catherine de Medicis and the deceased Henri II, to Henry of Navarre, a Huguenot and Bourbon. The wedding was intended to reconcile the parties in the religious wars that had raged for the past decade. The second event was the St Bartholomew's Day Massacre. This was a slaughter of Huguenot nobles who had come to Paris for the wedding; a massacre that would spread out into the countryside. It was instigated by none other than the mother of the bride, who convinced her son Charles IX that the Huguenots who had flooded into the capital for the wedding were actually there to usurp the throne. There were other contenders for this throne too. Neither of Charles's two younger brothers would have grieved his death, and Henri de Guise, leader of the Catholics and co-architect of the massacre, felt he also had a worthwhile claim.

This all allows lots of scope for cross and double cross, even without Dumas, but the author strides into it like the giant he was, rearranging political and romantic alliances, inventing an executioner as grateful for kindness as a puppy, and embellishing the sinister reputation of Catherine de Medicis even further. He uses two young men, M de la Mole and M Coconnas as his heroes. As in real life, one will have an affair with Marguerite, the other with the Duchesse de Nevers, providing the Dumas staples of romantic interest and male brotherhood onto death, this last a fiction in this case. He adds a level of intrigue by creating a political bond between Marguerite and her new husband, who will ignore each other's liasons as they did in real life, but in this case to advance their own causes and affairs without working against each other, while at the same time appearing to the court to be completely estranged.

The setting of the Louvre provides a superb backdrop for affairs and political intrigues, with characters able to spy, eavesdrop, visit and depart unnoticed, and even disappear from the world completely through hidden oubliettes. Read this for just plain fun and escape.

5. La Reine Margot by Alexandre Dumas translated from the French by David Bogue, 1846, "modernized and revised against the standard French text" of La Reine Margot, ed Claude Schopp, by David Coward

first published in serial form in La Presse from December 25, 1844 to April 5, 1845

finished reading January 24, 2018

The works of Alexandre Dumas are known for many things: adventure, romance, beautiful women, dastardly evil- doers. Accurate history is not one of his fortes. Dumas loved to take figures from history, imbue them with legendary characteristics, and toss them into a stew of fact and fiction. La Reine Margot is a perfect example.

The novel starts with two historic events. The first was the 1572 wedding of Marguerite de Valois, Catholic daughter of Catherine de Medicis and the deceased Henri II, to Henry of Navarre, a Huguenot and Bourbon. The wedding was intended to reconcile the parties in the religious wars that had raged for the past decade. The second event was the St Bartholomew's Day Massacre. This was a slaughter of Huguenot nobles who had come to Paris for the wedding; a massacre that would spread out into the countryside. It was instigated by none other than the mother of the bride, who convinced her son Charles IX that the Huguenots who had flooded into the capital for the wedding were actually there to usurp the throne. There were other contenders for this throne too. Neither of Charles's two younger brothers would have grieved his death, and Henri de Guise, leader of the Catholics and co-architect of the massacre, felt he also had a worthwhile claim.

This all allows lots of scope for cross and double cross, even without Dumas, but the author strides into it like the giant he was, rearranging political and romantic alliances, inventing an executioner as grateful for kindness as a puppy, and embellishing the sinister reputation of Catherine de Medicis even further. He uses two young men, M de la Mole and M Coconnas as his heroes. As in real life, one will have an affair with Marguerite, the other with the Duchesse de Nevers, providing the Dumas staples of romantic interest and male brotherhood onto death, this last a fiction in this case. He adds a level of intrigue by creating a political bond between Marguerite and her new husband, who will ignore each other's liasons as they did in real life, but in this case to advance their own causes and affairs without working against each other, while at the same time appearing to the court to be completely estranged.

The setting of the Louvre provides a superb backdrop for affairs and political intrigues, with characters able to spy, eavesdrop, visit and depart unnoticed, and even disappear from the world completely through hidden oubliettes. Read this for just plain fun and escape.

69thorold

>68 SassyLassy: Wonderful! We all need more books like that.

70NanaCC

>68 SassyLassy: That definitely sounds like a good story. I love when just enough actual history is thrown in to give a flavor of the time.

71chlorine

>68 SassyLassy: I'm glad you had a good time with this book!

72arubabookwoman

I'm very unschooled in French history. I've had La Reine Margot on the shelf for more than a few years, but haven't had the nerve to pick it up, though I'm sure it's very readable. There is a group read in the Category Challenge Group of Young Henry of Navarre by Heinrich Mann starting in January which I'm thinking of participating in since that's another one I've delayed reading. (The second volume will be another group read later in the year.)

73baswood

>68 SassyLassy: That ones on my French Bookshelf, enjoyed your review.

74.Monkey.

>68 SassyLassy: Dumas is great. :) I've only read three of his as yet (Monte Cristo, Musketeers, and The black tulip), but you know you're in for a good ride when you pick up something of his, haha.

>70 NanaCC: That's what Dumas' writing is, he plucked bits of history and made them suit his story desires, lol. So you go in knowing you won't be getting an accurate account, but there is an underlying base of history, with his romantic adventure on top. :P

>70 NanaCC: That's what Dumas' writing is, he plucked bits of history and made them suit his story desires, lol. So you go in knowing you won't be getting an accurate account, but there is an underlying base of history, with his romantic adventure on top. :P

75SassyLassy

Bruce Chatwin is another uncharted read for me. Over the years I have tried reading his work from time to time, but never succeeded. This one, clearly acknowledged as fiction, is the first one I've finished.

6. The Viceroy of Ouidah by Bruce Chatwin

first published 1980

finished reading January 26, 2018

One hundred and seventeen years after his death, Francisco Manoel da Silva's descendants still gathered yearly in Ouidah for a Requiem Mass and dinner in his honour. This was far more that an average family gathering, for when Dom Francisco died back in 1857, "... he left sixty-three mulatto sons and an unknown quantity of daughters, whose ever-darkening progeny {were} now numberless as grasshoppers".

This 'ever-darkening' aspect was one that worried the descendants, attached as they were to what they perceived to be their European origins, feeling that somehow this elevated them above the citizens of Dahomey, Nigeria, Zaire, Togo and other countries they had populated. The da Silvas clung to the past, calling themselves Brazilians, for that is where their ancestor had been born. They clung to this idea of whiteness, pointing to Dom Francisco's last surviving daughter, Mlle Eugenia da Silva, "... a skeleton who happened to breathe". The unthinkable was now happening, even as they feasted. Mlle Eugenia, their Mama Wéwé, was dying. They would have to drop all pretence.

Francisco da Silva had first come to the shores of what is now Benin in 1812. He represented a Brazilian company that bought slaves from the King of Dahomey to supply Brazilian planters, in exchange for guns, rum, and whatever else might take the King's fancy. Da Silva dreamed of returning to Bahia. In the meantime, he built a house, just like the his Brazilian partner's.

This all sounds as if the author sees Africa through imperial eyes, as a continent whose only purpose is to be exploited, whose people are as much a commercial resource as palm oil or gold. That may be true of the da Silvas, but Chatwin manages to give his tale a twist, so that the man who comes to make his fortune winds up a slave himself, a hostage to the King who has made him his blood brother, so tying him with invisible bonds to his macabre throne and to the country da Silva would plunder and flee.

There are many novels by non Africans of Africa defeating those who would exploit it. There are echoes of some of them here. This is Chatwin's first novel, and it is obvious Conrad and Greene were strong influences. However, it is also obvious Chatwin cannot equal either. At times, images of Flashman pop unbidden to mind. While Flashman fans are legion, it is probably not a style Chatwin was striving for. While at times the writing is lush, there is an off kilter feel to it, a feeling that Chatwin couldn't seem to decide between horror and adventure.

Perhaps this is in part because there was a real life Francisco Manoel da Silva, Francisco Féliz de Souza, whose descendants actually do gather annually to honour him. While Chatwin has his family mourning the "...Slave Trade as a lost Golden Age when their family was rich, famous and white", it is difficult to imagine today. Yet the website for the Ouidah Museum of History, after stating de Souza managed the slave trade for Dahomey, adds "To this day, the descendants of de Souza hold a place of importance in Ouidan society". Even Werner Herzog has taken on this story, with his 1987 Cobra Verde, with Klaus Kinski as da Silva. Not really recommended; in the end, this is probably a book best suited to Chatwin completists.

6. The Viceroy of Ouidah by Bruce Chatwin

first published 1980

finished reading January 26, 2018

One hundred and seventeen years after his death, Francisco Manoel da Silva's descendants still gathered yearly in Ouidah for a Requiem Mass and dinner in his honour. This was far more that an average family gathering, for when Dom Francisco died back in 1857, "... he left sixty-three mulatto sons and an unknown quantity of daughters, whose ever-darkening progeny {were} now numberless as grasshoppers".

This 'ever-darkening' aspect was one that worried the descendants, attached as they were to what they perceived to be their European origins, feeling that somehow this elevated them above the citizens of Dahomey, Nigeria, Zaire, Togo and other countries they had populated. The da Silvas clung to the past, calling themselves Brazilians, for that is where their ancestor had been born. They clung to this idea of whiteness, pointing to Dom Francisco's last surviving daughter, Mlle Eugenia da Silva, "... a skeleton who happened to breathe". The unthinkable was now happening, even as they feasted. Mlle Eugenia, their Mama Wéwé, was dying. They would have to drop all pretence.

Francisco da Silva had first come to the shores of what is now Benin in 1812. He represented a Brazilian company that bought slaves from the King of Dahomey to supply Brazilian planters, in exchange for guns, rum, and whatever else might take the King's fancy. Da Silva dreamed of returning to Bahia. In the meantime, he built a house, just like the his Brazilian partner's.

This all sounds as if the author sees Africa through imperial eyes, as a continent whose only purpose is to be exploited, whose people are as much a commercial resource as palm oil or gold. That may be true of the da Silvas, but Chatwin manages to give his tale a twist, so that the man who comes to make his fortune winds up a slave himself, a hostage to the King who has made him his blood brother, so tying him with invisible bonds to his macabre throne and to the country da Silva would plunder and flee.

There are many novels by non Africans of Africa defeating those who would exploit it. There are echoes of some of them here. This is Chatwin's first novel, and it is obvious Conrad and Greene were strong influences. However, it is also obvious Chatwin cannot equal either. At times, images of Flashman pop unbidden to mind. While Flashman fans are legion, it is probably not a style Chatwin was striving for. While at times the writing is lush, there is an off kilter feel to it, a feeling that Chatwin couldn't seem to decide between horror and adventure.

Perhaps this is in part because there was a real life Francisco Manoel da Silva, Francisco Féliz de Souza, whose descendants actually do gather annually to honour him. While Chatwin has his family mourning the "...Slave Trade as a lost Golden Age when their family was rich, famous and white", it is difficult to imagine today. Yet the website for the Ouidah Museum of History, after stating de Souza managed the slave trade for Dahomey, adds "To this day, the descendants of de Souza hold a place of importance in Ouidan society". Even Werner Herzog has taken on this story, with his 1987 Cobra Verde, with Klaus Kinski as da Silva. Not really recommended; in the end, this is probably a book best suited to Chatwin completists.

76baswood